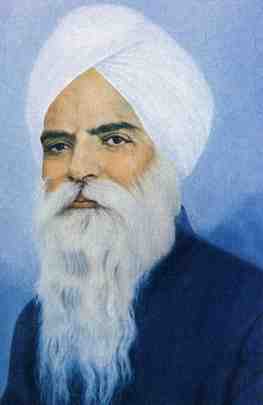

Bhai Vir Singh was a poet, scholar and exegete, a major figure in the Sikh renaissance and in the movement for the revival and renewal of Punjabi literary traditioin. His identification with all the important concerns of modern Sikhism was so complete that he came to be canonized as Bhai, the Brother of the Sikh Order, very early in his career. For his pioneering work in its several different genres, he is acknowledged as the creator of modern Punjabi literature.

Born on 5 December 1872, in Amritsar, Bhai Vir Singh was the eldest of Dr Charan Singh’s three sons. The family traces its ancestry back to Diwan Kaura Mall (d. 1752), who rose to the position of vice-governor of Multan, under Nawab Mir Mu’ln ul-Mulk, With the title of Maharaja Bahadur. Baba Kahn Singh (1788-1878) was perhaps the first in the family to be regularly sworn a Sikh. He turned a recluse when he was still in his early teens and spent his entire youth in monasteries at Haridvar and Amritsar acquiring training in traditional Sikh learning. His mother’s affection ultimately reclaimed him to the life of a householder at the age of 40, when he got married. Adept in versification in Sanskrit and Braj as well as in the oriental system of medicine, Baba Kahn Singh passed on his interests to his only son, Dr Charan Singh. Apart from his sustained involvement in literary and scholarly pursuits, mainly as a Braj poet, Punjabi prose-writer, musicologist, prosodist and lexicographer, Dr Charan Singh took active interest in the affairs of the Sikh community, then experiencing a new urge for restoration as well as for change.

To this patrimony of Bhai Vir Singh was added from his mother’s side a living kinship With another rich tradition of scholarship in exegesis of the Ckiani school, going back to the times of Guru Gobind Singh. His maternal grandfather Giani Hazara Singh compiled a lexicon of Guru Granth Sahib, and wrote a commentary on Bhai Gurdas Varan. As a schoolboy, Bhai Vir Singh used to spend a great deal of his time in the company of Giani Hazara Singh under whose guidance he not only learnt the classical and neo-classical languages, Sanskrit, Persian and Braj, but also received grounding, both theoretical and practical, in the science of Sikh exegesis.

Bhai Vir Singh was the child of an age in ferment. The extinction of Sikh sovereignty in the Punjab, the decline in the fortunes of Sikh aristocracy, the gradual emergence of urban middle classes, the dissipation of the "national intellectual life" of the Punjab owing to the neglect and decay of indigenous education of the local people from their political destiny aroused among the Sikhs concern for survival and for redefining the boundaries of their faith. Further challenges arose in the shape of modernization, of Christian, Muslim and Hindu movements of proselytization and the agnostic cults such as Brahmo Samaj. Parallel to the developments foreboding gradual appropriation of Sikhism by the Hindu social order emerged a powerful end towards Braj classicism in the Sikh literary and sdlolarly tradition. Mythologization of the persons of Sikh Gurus, mixing of fiction with historical fact and interweaving of Vedantic and Vaisavite motifs into the essential Sikh teaching were its typical features. The response arose in Sikhism several movements- Nirankari (puritanism),Namdhari (militant protestantism), Singh Sabha (revivalism and renaissance) and Panch Khalsa Diwan (aggressive fundamentalism) .

Bhai Vir Singh had the benefit of both the traditional indigenous learning as well as of modern English education. He learnt Persian and Urdu from a Muslim Maulawi in a mosque and was apprenticed to Giani Harbhajan Singh, a leading classical scholar, for Sanskrit and Sikh literature. He then joined the Church Mission School, Amritsar and took his matriculation examination in 1891. At school, the conversion of some of the students provect a crucial experience which strengthened his own religious conviction. From the Christian missionaries emphasis on literary resources, he learnt how efficacious the written word could be as a means of informing and influencing a person’s innermost being. Through his English courses, he acquired familiarity with modern literary forms, especially short lyric. While still at school, Bhai Vir Singh was married at the age of 17 to Chatar Kaur daughter of Sardar Narain Singh of Amritsar.

Unlike the educated young men of his time, Bhai Vir Singh was not tempted by prospects of a career in government service. He chose for himself the calling of a writer and created material conditions for a single minded pursuit of it. An year after his passing the matriculation examination, he set up a lithograph press in collaboration with Bhai Wazir Singh, a friend of his father’s. As his first essays in the literary field, Bhai Vir Singh composed somc Geography textbooks for schools.

Bhai Vir Singh began taking active interest in the affairs of Singh Sabha movement. To promote its aims and objects, he launched in 1894 the Khalsa Tract Society. In November 1899, he started a Punjabi weekly, the Khalsa Samachar. He was among the principal promoters of several of the Sikh institutions, such as Chief Khalsa Diwan, Sikh Educational Society (1908) and the Punjab and Sind Bank (1908). Interest in corporate activity directed towards community development remained Bhai Vir Singh’s constant concern, simultaneously with his creative and scholarly pursuits. In this engagement and, at the same time, in his eschewal of political activity, the Christian missionary example was apparently his model.

In determining the basic parameters of the modern phase of Sikhism, Bhai Vir Singh stressed the autonomy of Sikh faith nourished and sustained by an awakening amongst the Sikhs of the awareness of their distinct theological and cultural identity. Secondly, he aimed at reorienting the Sikhs’ understanding of their faith in such a manner as to help them assimilate the different modernizing influences to their historical memory and cultural heritage. Education of the masses was the first requirement for the fulfilment of these objectives. In the meanwhile, the old educational system which had till then served as a channel for communication of the traditional knowledge to the youth of the race had broken down with the withdrawal, under British dispensation, of state patronage from the indigenous institutions, As if to fill the vacuum as well as to build new channels of intra-community communication, Bhai Vir Singh through his single-minded cultivation of Punjabi language as the medium of his theological, scholarly and creative work, resolved the cultural dilemma which the Sikhs faced at the turn of the century. On the one hand was the Sikh literary tradition in Braj language which had collected unmatched riches in multiple directions during the course of its three-centuries-long elitist career, on the other were the compulsions for mobilizing the common Sikhs through their own language. By drawing upon the Sikh tradition of Braj literature for his basic inspiration and cultural motivation and upon the Punjabi literary tradition for its linguistic components Bhai Vir Singh initiated a new literary idiom distinctly different from both. The tracts produced by the Khalsa Tract Society introduced a down to earth literary Punjabi remarkable for lightness of touch as well as for freshness of expression. In this writing lay the beginnings of modern Punjabi prose.

The Khalsa Tract Society periodically made available under the title Nirguniara lowcost publications on Sikh theology, history and philosophy and on social and religious reforrn. Through this journal Bhai Vir Singh established a living contact with an everexpanding circle of readers. He used the Nirguniara as a vehicle for his own self expression and some of his major creative works such as the epic Rana Surat Singh, the novel Baba Naudh Singh, and the lives of the Gurus Sri Guru Nanak Chamatkar and Sri Guru Kalgidhar Chamatkar were originally serialized in its columns.

In literature, Bhai Vir Singh started as a writer of romances which proved to be the forerunners of the Punjabi novel. His writings in this genre- Sundari (1898), Bijay Singh (1899), Satvant Kaur (published in two parts, I in 1900 and II in 1927)- were aimed at recreating the heroic period (eighteenth century) of Sikh history. Through these novels he made available to his readers typical models of courage, fortitude and human dignity.

Subhagji da Sudhar Hathin Baba Naudh Singh, popularly known as Baba Naudh Singh (serialized in Nirguniara from 1907 onwards and published in book form in 1921) shares with Rana Surat Singh ( which he had started serializing two years earlier), Bhai Vir Singh’s fascination with the theme of widow’s desperate urge for a re-union with her dead husband. But in Baba Naudh Singh this search is situated in a more mundane setting. This makes all the difference. The narrative here is more realistic in tone, and almost contemporary in its appeal. Bhai Vir Singh weaves into the narrative numerous motifs of social reforms moral teaching and religious preaching and depicts several situations of intercommunal and urban-rural confrontation. In 1905, Bhai Vir Singh started serializing through tracts Rana Surat Singh, the first Punjabi epic, written in blank verse of Sirkhand, variety. This long narrative of over 14,000 lines is a striking imaginative evocation of the situation of the Sikhs through a symbolic tale of a widowed queen in quest of her lost paradise. The spiritual voyage of Rani Raj Kaur, the main protagonist of the poem, from external factuality to internal essence has been described by Bhai Vir Singh in the form of a fantasy of spiritual ascension. Apart from living out her earthly destiny of suffering and pain, she symbolized the total ethos of the Sikh people at that historical moment when they were emerging out of their sense of defeat and despair into an era of a fresh beginning.

Bhai Vir Singh’s quest for new forms of expression continued. Soon after the pubtication of Rana Surat Singh in book form in 1919, he turned to shorter poems and Lyrics. In quick succession came Dil Tarang (1920), Earel Tupke ( 1921), Lahiran de Har (1921), Matak Hulare (1922), and Bijlian de Har (1927). Following at some distance was Mere Salan Jio (1953). In this poetry, Bhai Vir Singh’s concerns were more aesthetic than didactic, metaphysical or mystical. He refined the old verse forms and created new ones. The metrical patterns Kabir, Soratha, Baint, etc., which he inherited from classical Punjabi literature, were transformed into lights nimble measures. Bhai Vir Singh also naturalized in Punjabi the Rubai which he borrowed from Urdu. By grafting Soratha and Sirkhandv forms on English blank verse, he paved the way for the emergence of Punjabi poem. As it happened, the first play written in Punjabi, Raja Lakhdata Singh (1910)* also came from the pen of Bhai Vir Singh. Tentative in form, the 1. play did reveal the author’s powers of constructing crisp and witty dialoguesb Change-over from Braj Bhasa to Punjabi 2. as the main medium of Sikh literary and 3. scholarly expression created the need for new materials such as glossaries, lexicons, encyclopaedias and exegetical works. Bhai Vir Singh himself provided several of the tools. He revised and enlarged Giani Hazara Singh’s dictionary, Sri Guru Granth Kosh, originally published in 1898. The revised version, published in 1927, gave evidence of Bhai Vir Singh’s command of the science of etymology and of the classical and modern languages. He published critical editions of some of the old Sikh texts such as Sikhan di Bhagat Mala (1912), Prachin Panth Prakash (1914), Puratan Janam Sakhi (1926) and Sakhi Pothi (1950).

Monumental in size and scholarship was his annotation of Bhai Santokh Singh’s magnum opus, Sn Gur Pratap Suraj Granth, published from 1927 to 1935 in fourteen volumes covering 6668 pages.

No sooner was the Sri Gur Pratap Suraj Grallth completed than Bhai Vir Singh launched on an even more arduous task. This was a detailed commentary on the Guru Granth Sahib. In a way, exegesis had been his lifelong occupation. Early in his career he had annotated selections from the Holy Book published in 1906 under the title Panj Granth Saiik, and, as he himself declared, all of his writing was an exposition of the Sikh Scripture. He devoted himself unsparingly to the commentary, but it remained unfinished. A lifetime of unrelieved hard work and the weight of advancing years at last began to tell. In early 1957 signs of fatigue and weakness appeared. He was taken ill with a fever and died in his home in Amritsar on 10 June 1957. The portion of the commentary- nearly one half of the Holy Book- he had completed was published posthumously in seven large volumes.