Anti Sikh Pogrom 1984

Sequence of Events

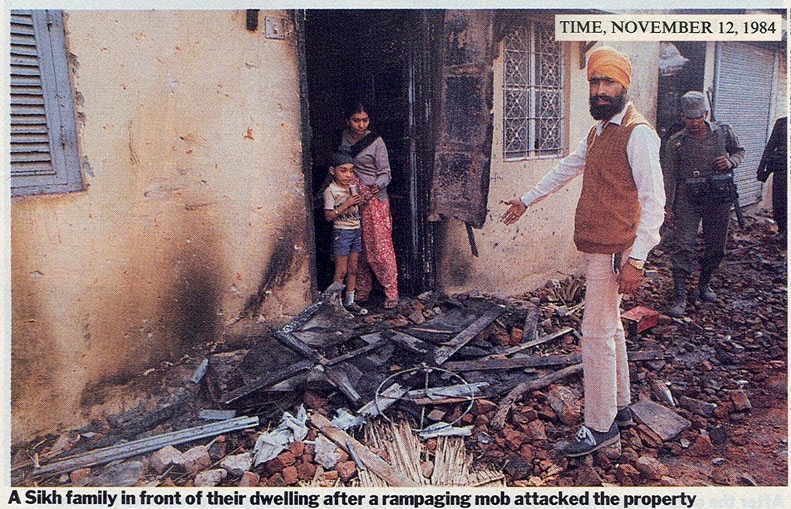

A recapitulation of the 1984 Delhi carnage in which about 4,000 Sikhs were massacred in three days in the wake of Indira Gandhi’s assassination.

October 31, 1984:

9.20 am: Indira Gandhi was shot by two of her security guards at her residence No. 1, Safdarjung Road, and rushed to All India Institute of Medical Sciences.

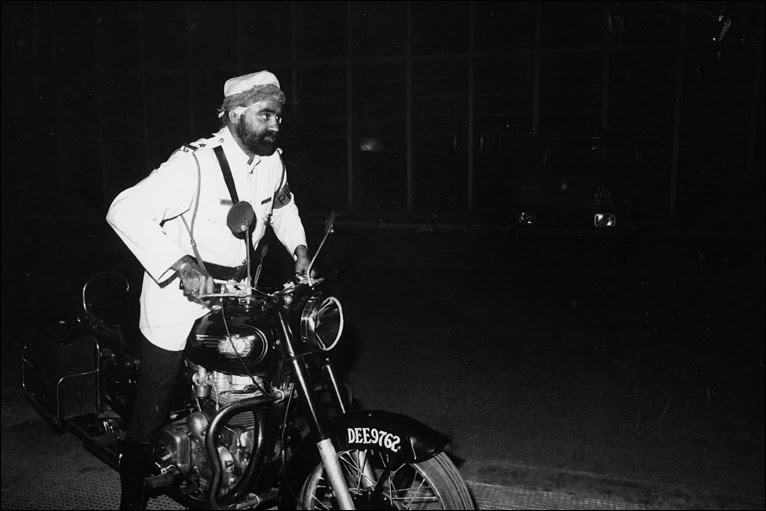

11 am: Announcement on All India Radio specifying that the guards who shot Indira Gandhi were Sikhs. A big crowd was collecting near AIIMS.

2 pm: Though her death was yet to be confirmed officially, it became common knowledge because of BBC bulletins and special afternoon editions of newspapers.

4 pm: Rajiv Gandhi returned from West Bengal and reached AIIMS. Stray incidents of attacks on Sikhs in and around that area.

5.30 pm: The cavalcade of President Zail Singh, who returned from a foreign visit, was stoned as it approached AIIMS.

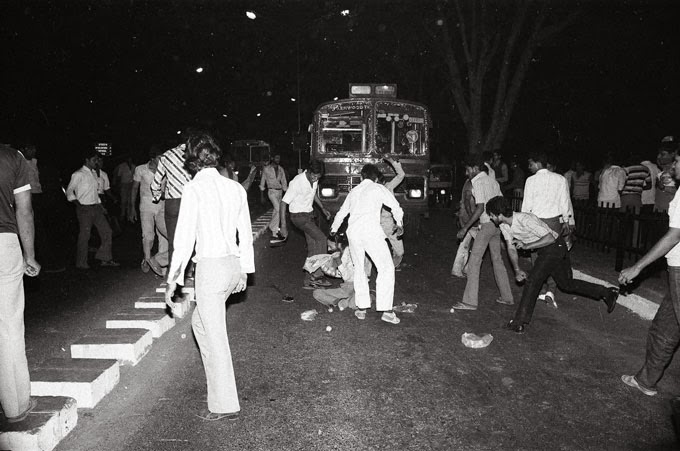

Late evening and night: Mobs fanned out in different directions from AIIMS. The violence against Sikhs spread, starting in the neighbouring constituency of Congress councillor Arjun Dass. The violence included the burning of vehicles and other properties of Sikhs. That happened even in VIP areas like the crossroads near Prithviraj Road where cars and scooters belonging to Sikhs were burnt.

Shortly after Rajiv Gandhi was sworn in as Prime Minister, senior advocate and Opposition leader Ram Jethmalani met home minister P.V. Narasimha Rao and urged him to act fast and save Sikhs from further attacks. Delhi’s lt governor P.G. Gavai and police commissioner S.C. Tandon visited some of the violence-affected areas. Despite all these developments, no measures were taken to control the violence or prevent further attacks on Sikhs throughout the night between October 31 and November 1.

November 1, 1984:

Several Congress leaders held meetings on the night of October 31 and morning of November 1, mobilising their followers to attack Sikhs on a mass scale. The first killing of a Sikh reported from east Delhi in the early hours of November 1. About 9 am, armed mobs took over the streets of Delhi and launched a massacre. Everywhere the first targets were Gurudwaras – to prevent Sikhs from collecting there and putting up a combined defence.

Mobs were armed with iron rods of a uniform size. Activist editor Madhu Kishwar saw some of the rods being distributed among the miscreants. Mobs also had an abundant supply of petrol and kerosene. Victims traced the source of kerosene to dealers belonging to the Congress party. For instance, a Congress worker called Brahmanand Gupta, a kerosene dealer, figures prominently in affidavits filed from Sultanpuri.

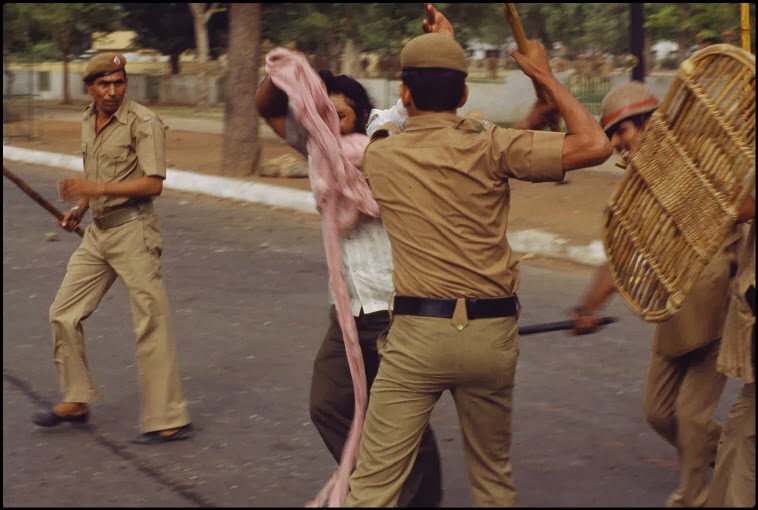

Every police station had a strength of about 100 men and 50-60 weapons. Yet, no action was taken against miscreants in most places. The few places where the local police station took prompt measures against mobs, hardly any killings took place there. Farsh Bazar and Karol Bagh are two such examples. But in other localities, the priority of the police, as it emerges from the statement of the then police commissioner S.C. Tandon before the Nanavati Commission, was to take action against Sikhs who dared to offer resistence. All the Sikhs who fired in self-defence were disarmed by the police and even arrested on trumped up charges.

Mobs generally included teams attending to specific tasks. When shops were to be looted, the first team that gets into action would kill and remove all obstacles. The second team specialises in breaking locks. The third team would engage in looting. And the fourth team would set the place on fire.

Most of the mobs were led by Congress members, including those from affluent families. For instance, a Youth Congress leader called Satsangi led a mob in the posh Maharani Bagh. The worst affected areas were however far flung, low income colonies like Trilokpuri, Mongolpuri, Sultanpuri and Palam Colony.

The Congress leaders identified by the victims as organisers of the carnage include three MPs H.K.L. Bhagat, Sajjan Kumar and Dharam Dass Shastri and 10 councillors Arjan Dass, Ashok Kumar, Deep Chand, Sukhan Lal Sood, Ram Narayan Verma, D.R. Chhabbra, Bharat Singh, Vasudev, Dharam Singh and Mela Ram.

November 2, 1984:

Curfew was in force throughout Delhi – but only on paper. The Army was also deployed throughout Delhi but nowhere was it effective because the police did not co-operate with the soldiers who were not empowered to open fire without the consent of senior police officers or executive magistrates. Meanwhile, mobs continued to rampage with the same ferocity.

November 3,1984:

It was only towards the evening of November 3 that the police and the Army acted in unison and the violence subsided immediately after that. Whatever violence took place the next two or three days was on a much smaller scale and rather sporadic.

Aftermath of the carnage:

Most of the arrested miscreants were released at the earliest. But the Sikhs arrested for firing in self-defence generally remained in detention for some weeks. Worse, there was also a pattern throughout Delhi of the police not registering proper cases on the complaints of victims. Instead, the police registered vaguely worded omnibus FIRs which did not deal with any specific incident or person. As if the damage done by such FIRs was not bad enough, the police made little effort to investigate the cases and trace the miscreants. The only acknowledgement of any wrongdoing on their part was the appointment of a committee headed by senior police officer Ved Marwah to probe the role of the police.

Two remarkable initiatives that came on the same month as the carnage, in a bid to make up for the failure of the Government, were from human rights organisations and a leading Opposition party. People’s Union of Civil Liberties and People’s Union for Democratic Rights came out with a devastating expose in a booklet titled, Who are the guilty? The Bharatiya Janata Party contradicted the Government’s claim then that only 600 people were killed in the Delhi carnage. On the basis of a survey done by its cadres, the BJP came out with a death toll of 2,700, which is remarkably close to the official tally of 2,733 arrived at three years later.

On December 27, 1984, the Lok Sabha elections were held and the Congress party had a landslide victory bagging over 400 seats for the first and so far the only time in the Indian electoral history. The election held under the shadow of Indira Gandhi’s assassination and the subsequent massacre was marked by an anti-Sikh sentiment whipped up by the Congress party campaign.

In the early months of 1985, two more NGO reports followed: one by Citizens for Democracy headed by Justice V.M. Tarkunde and another by a Citizens’ Commission headed by former chief justice of India S.M. Sikri. Both indicted the Government and the ruling party and called for a judicial inquiry.

A journalist, Rahul Kuldeep Bedi, filed a writ petition in the Delhi high court seeking an inquiry into the role of the police. PUDR filed a writ petition in the same court seeking a direction to the Government to appoint a Commission of Inquiry. Both the petitions were dismissed.

On April 26, 1985, i.e. almost six months after the carnage, the Rajiv Gandhi Government appointed the Ranganath Misra Commission to inquire into “the allegations in regard to the incidents of organised violence” in Delhi.

In June 1985, a group of eminent persons and representative of human rights organisations came together under the banner of the Citizens Justice Committee (CJC) to help the Misra Commission unravel the truth.

The Misra Commission held all its proceedings in camera and took the help of the CJC to get affidavits from victims.

On March 31, 1986, the CJC notified its withdrawal as the Misra Commission kept it out of most of the inquiry holding “in camera proceedings within in camera.”

In August 1986, the Misra Commission submitted its report to the Government, which in turn tabled it in Parliament in February 1987. The report vindicated the CJC’s apprehension that the Misra Commission would whitewash the role of the Government and the ruling Congress party.

On February 23, 1987, the Government appointed three committees on the recommendation of the Misra Commission. (1) Jain-Banerjee committee to pursue cases that have either not been registered or not properly investigated. (2) Kapur-Mittal committee to identify delinquent police officials. (3) Ahooja committee to arrive at the official death toll of the carnage.

In August 1987, the Ahooja committee determined that the number of persons killed in Delhi in the 1984 carnage were 2,733.

In November 1987, the Delhi high court stayed the functioning of the Jain-Banerjee committee because of its very first recommendation, which was to register a murder case against former Congress MP Sajjan Kumar. The petition was filed by one of the co-accused, Brahmanand Gupta.

In October 1989, the Delhi high court quashed the notification appointing the Jain-Banerjee committee. The court found that the powers of monitoring of investigation and the institution of new case conferred on the committee were illegal.

March 1, 1990: The two members of the Kapur-Mittal committee gave separate reports. Justice Dalip Kapur gave no finding on the ground that the committee had not been empowered to summon police officials to hear their version. Kusum Lata Mittal identified 72 police officials, including six IPS officers, recommending various penalties against them.

March 27, 1990: The Delhi Administration prompted by the newly elected V.P. Singh Government appointed the Poti-Rosha committee without the legal defects pointed out by the high court in the case of the Jain-Banerjee committee.

August-September 1990: The Poti-Rosha committee sent two batches of recommendations covering altogether 30 affidavits, including the case against Sajjan Kumar. When a CBI team went to his house to arrest him, Sajjan Kumar and his supporters locked up the officials and detained them till his lawyer, R.K. Anand (now a Congress MP), obtained “anticipatory bail” from the high court. Subsequently, the two committee members, Subramaniam Poti and Padam Rosha, declined to carry on in office when their first term expired on September 22.

October-November 1990: The Delhi Administration constituted a fresh committee comprising J.D. Jain and D.K. Aggarwal, to take over the work of the Poti-Rosha committee.

June 30, 1993: After making recommendations from time to time from among the remaining 1,000-odd affidavits, including 21 affidavits against Congress leaders H.K.L Bhagat and Sajjan Kumar, the Jain-Aggarwal committee submitted a detailed report giving a comprehensive account of how the police scuttled carnage cases at the stages of registration, investigation and prosecution. The Jain-Aggarwal committee also recommendation action several police officials for their lapses.

1994: The Delhi Government under Madan Lal Khurana appointed an Advisory Committee under the chairmanship of Justice R.S. Narula. The Advisory Committee reviewed the status of the recommendations made the Poti-Rosha committee, Jain-Aggarwal committee and Kapur-Mittal committee. The Advisory Committee also made a particular reference to the failure of the police, which came under the Congress-ruled Central government, to book the cases recommended against Congress leaders H.K.L. Bhagat and Sajjan Kumar.

1995: On the basis of the Advisory Committee’s report, Delhi chief minister Madan Lal Khurana repeatedly asked the Centre to let the police take action on the 21 affidavits against Congress leaders H.K.L. Bhagat and Sajjan Kumar. It was only when Khurana threatened to complain to the National Human Rights Commission, the Centre sent those affidavits to the Delhi Government.

2000: The Atal Behari Vajpayee Government appointed a fresh judicial inquiry into the 1984 carnage under the chairmanship of Justice G.T. Nanavati. The justification offered for it was the failure to punish the guilty. Despite the lapse of over 15 years, the Nanavati Commission received hundreds of fresh affidavits from victims as well as victims, including prominent persons such as I.K. Gujral, Khushwant Singh, Kuldip Nayar and Jagjit Singh Aurora.

2001-02: The Nanavati Commission records much damaging evidence brought on record for the first time since 1984. Arguments pending at the time of release of this report.